Top performers in an industry command top dollar. It sounds simple, but what defines a top performer? Mark Tibergien and Owen Dahl note in How to Value, Buy or Sell a Financial Advisory Practice that “value – like beauty – is in the eye of the beholder, but the principles of valuation have been consistent for many years.” What can we learn from those principles to improve a business?

There are many reasons to focus on value. Sales of businesses regularly show up in the news. Mergers and acquisitions get the big headlines, but they are not the only reasons to measure the value of a firm. Privately-held businesses must all address succession planning. Growth plans also often come with the need to raise capital. In either of those circumstances, you will need to consider the value of your firm, both to protect your own interests and to help the “investor” (new owner or source of capital) consider their investment.

Fair value allows the party with the capital to get a return that compensates them sufficiently for the use of their capital. If you are considering bringing a partner into a business, they must decide how long it will take them to recoup the investment they make in the business. The new partner that commits capital thinks about the risks inherent in putting their money into the business and compares the expected returns to their other investment opportunities.

Valuation is both an art and a science. A discounted cash flow model (DCF) uses all revenue and expenses of the business. The cash flows are forecasted out a number of years and discounted back to present value. Because DCF uses forecast numbers, there is scrutiny over every input. It can be a complicated model, but it tends to be the most precise.

A multiple model is a shortcut for DCF and it values a business based on either revenue or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). The actual multiple applied is based on market data about similar transactions. It is a simpler exercise, but the real art is picking the multiple. The multiples used always fall into ranges.

Top performers recognize the levers used to value businesses. An increase in value comes mathematically from increasing the base revenue/earnings. It also comes from positioning the business to command multiples at the high end of the range, rather than the low end. For example, assume that a business has earnings of $75,000. Multiples range from 4 to 6 times earnings. At the low end of the range of multiples, the business is worth $300,000 today.

Focusing on the drivers that move the multiple up could increase the value to $450,000 without even adding earnings. Improving earnings to $100,000 a year would increase value to $400,000 at the low end of the range. Showing that the business is a top performer that should command high multiples would increase the value to $600,000. The multiplier of doing both at the same time can really pay off.

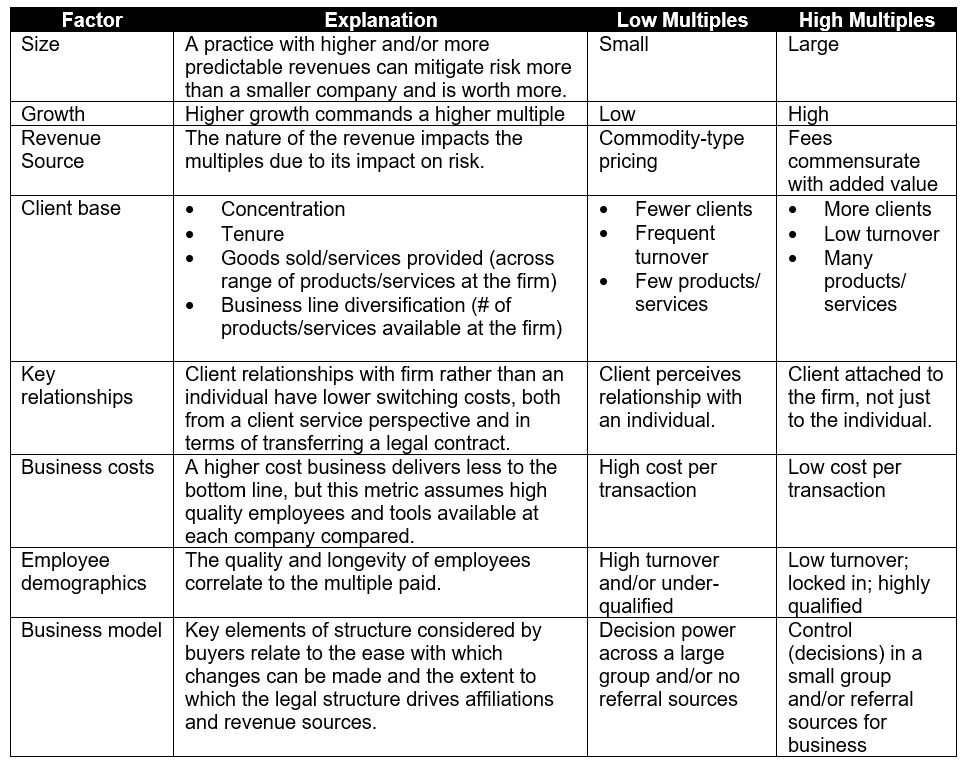

With the multiplier effect in mind, top performers focus on growing revenue and earnings in a way that moves them to higher valuation multiples at the same time. Following is a chart that shows some of the factors that can influence multiples.

The underlying principle behind the higher multiples is an increase in future value expected to be generated and/or a decrease in the risk of achieving the future earnings. And generating earnings is the key. Think back to an investor determining how long it will take to recoup their investment. Revenues are a nice measure and are more comfortable to disclose to the public, but earnings are required to pay back an investment.

A large practice with high growth that has proven sustainable over several years will be valued using a much higher multiple than a small business that has remained at the same size. Future growth is more likely in a business with a proven track record of generating new business. That makes the investment more profitable and less risky. That driver is more intuitive than some of the others in the chart above. Following are some examples that dive in a bit more deeply.

Generally, buyers and investors value a client base that has demonstrated low turnover and a willingness to use a wide range of products/services. Having a larger client list is normally more valuable, too, unless there are so many small clients that they are very costly to serve. A buyer would try to project out how much in revenue can be expected to be generated from the existing client list. This value is diminished if the clients are likely to leave the firm within a short time. The buyer also considers the firm’s ability to attract new clients – the infrastructure and name recognition. This is proven by having actually attracted the clients in the past.

Some of the factors above can work in tension with each other. For example, high growth may be most possible in a niche that has a high cost to deliver the business. Each business must define its own focus and be able to demonstrate that the benefits of a conflict outweigh the costs. The high growth may be so sustainable that it adds value despite the associated high costs. Or, the high costs could be temporary and changes to the business model or tools would drive the cost per transaction down over the long run.

Investment in the tools used by employees or in new lines of business demonstrates the complexity of the valuation models. On the surface, a business with higher quality tools would seem to be more valuable than one lacking such tools. The key, however, is to prove the value that the tools would add to the bottom line. This has much more credibility when actual profits have been earned than through forecasts. Otherwise, it tends to look like a business with unnecessarily high costs per transaction.

Top performers consider the short-, medium-, and long-term impacts of changes that they make in the business. They understand how to define success from new initiatives and rigorously review results to ensure they are successful. They also periodically assess the underlying business against a framework such as the one shown in the chart above. This ensures a clear view of their value and allows for some benchmarking against competitors.

Regardless of the business challenge you face, a framework that puts your decisions into the context of the value of your firm may simplify decisions and improve your net worth.